After sweeping the Italian press with rave reviews, I returned from Pesaro feeling as I had when How To Be Louise had been invited to be in competition at Sundance: my career was assured. I would soon be joining Susan Seidelman, Jim Jarmusch and the new generation of New York film directors.

With an active eighteen month old, it took a while to notice that the phone wasn’t ringing off the hook for the first step of that plan to go into effect:

Where were the offers of distribution? Figuring I should strike where the iron was most hot, I asked around about Italian distributors and called Lucky Red, a film distribution company in Italy, who’d been highly recommended as ‘right up my alley’. As I remember, the phone call wasn’t exactly a love fest but hey, the language barrier was certainly an issue. I mailed them hard copies of the press, a VHS tape and a very good letter.

In the meantime, I started cold-calling and mailing off VHS copies of the film and the press to distribution companies in the States. Janet Grillo at New Line Cinema got right back to me. “I don’t know. It’s not for New Line. it’s … it’s PETITE.” Petite? Hey are we talking about dresses or my life’s work? What the heck, New Line distributes Nightmare on Elm Street. I vowed to be more careful about which companies I approached.

Dan Talbot of New Yorker Films liked what he saw and told me over the phone: “If you get a good review in The New York Times, I’ll distribute this film.” Wow. YESSS. New Yorker Films! Reputable. Solid. First class!

My job instantly narrowed: 1) find a New York City film programmer who would show HTBL so it would get a review in the Times or 2) ‘four-wall’ it (Rent a movie theatre for a long-enough run so that HTBL can qualify for newspaper reviews.) The bad thing about option number two is that you have to lay out a fair amount of cash to rent the theatre and then (this is the pre-internet era) spend a huge amount of energy trying to tell everyone you know about it as well as make up ads and pay newspapers to run them to get an audience in there to defray the cost of the four-wall.

Just making this film I had gone to the mat with the begging and borrowing for the past four years. I’d thought my job was to make the darn film. I picked up the phone and started calling all the independent theatres: Bleecker Street Cinema, Cinema Village, The Quad and the newcomer, Anthology Film Archives. I mailed or Frank and I hand-delivered VHS/press packages.

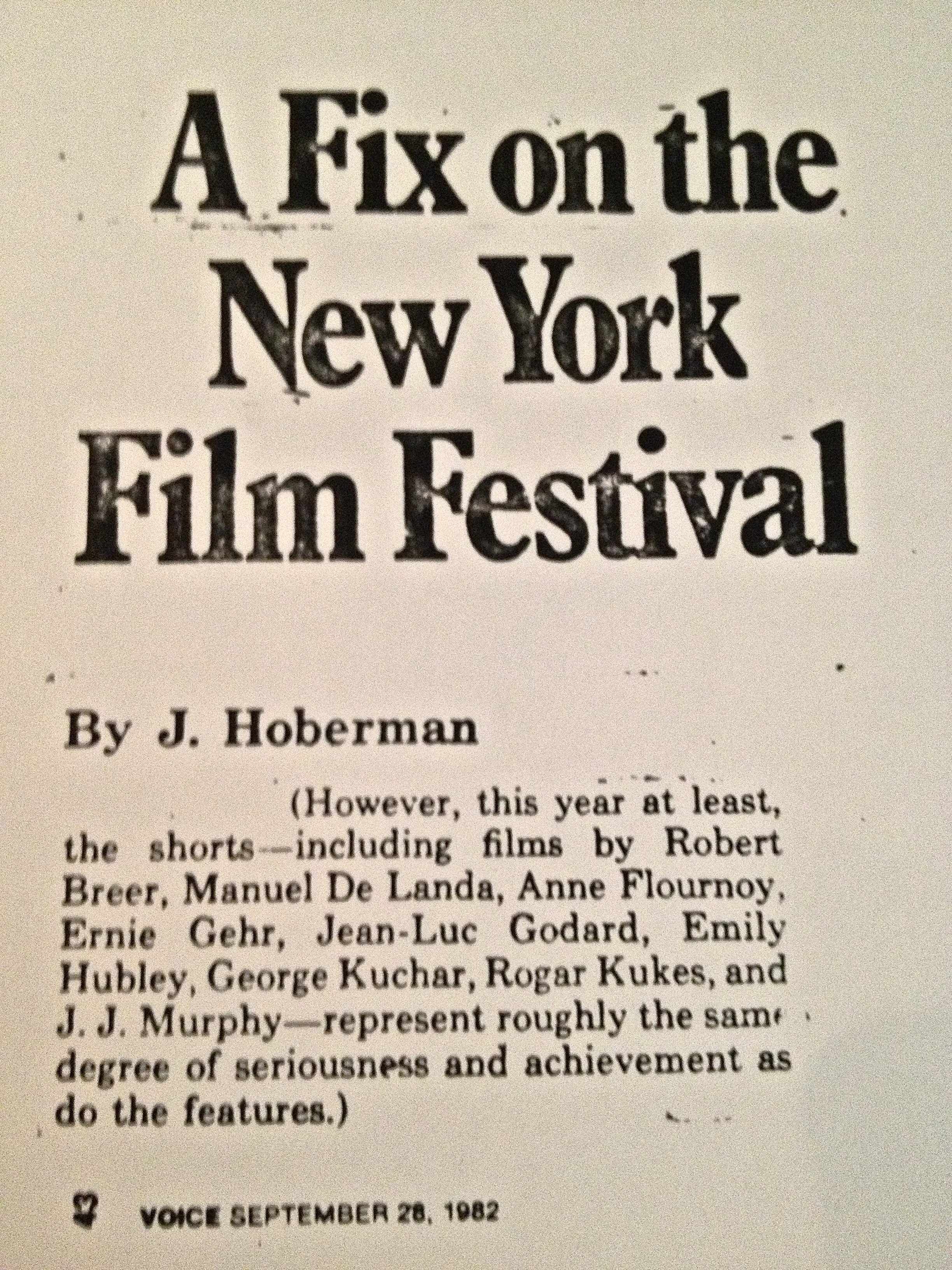

Jackie Raynal, who had been on the crew of so many of my favorite early Godard films I had watched at her Bleecker Street Cinema, was the first to call. She loved the film and wanted to invite Mr. Green and me to her Central Park South apartment for drinks. It was all very understated, all very restrained but I’m telling you, it was a love fest. Jackie is French, Jackie is sophisticated, Jackie is a woman. Jackie felt that people in France would go crazy for this film and she and her husband Sid Geffen were interested in talking about launching it at the Bleecker Street and then distributing it.

My first New York apartment had been just off Bleecker Street. I’d gone to art school in Paris and my family name is French. The Bleecker Street Cinema was my favorite downtown movie theatre. It was all coming together.

(to be continued)

Click the 'Like' button. (You get an instant surprise.)