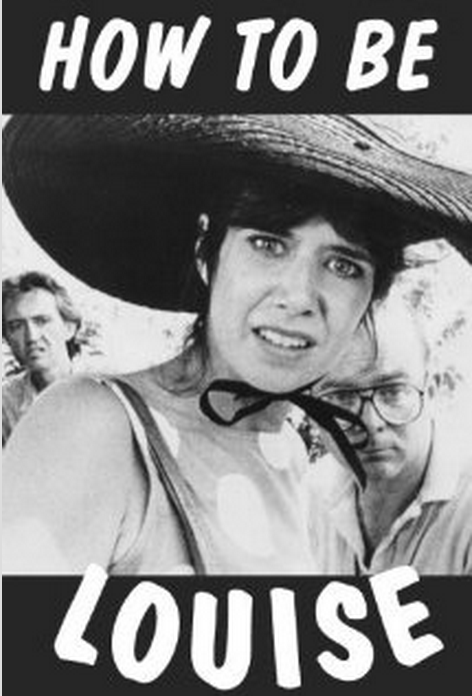

Before continuing with this saga, I want to backtrack to explain the difficult beginnings of making my first feature, How To Be Louise, which was eventually invited to be in the Dramatic Competition at Sundance. To this workaholic, the astonishing fact is that it wasn’t effort but rather surrender which made it possible.

Lea Floden as Louise with (l. to r.) Michael Moneagle and William Zimmer

As a young artist in my twenties, I had a clarity that my life would be devoted to art. I had no interest in being married and less than no interest in having children. Anyone can see that children are a huge distraction not to mention expensive, noisy and so demanding that, unless you have a lot of help, you can forget about your own agenda. Why would any woman with a dream shoot herself in the foot by having a baby, GOD FORBID more than one?

And then I turned thirty. Like a rogue wave, the biological desire to have children turned me upside down. I decided to try to find a man. And then one day, I surprised myself by flirting with a handsome guy who held the door for me as I walked into the wonderful artist-run restaurant that used to be on the corner of Prince and Wooster in Soho, FOOD.

Fast-forward to the year before we shot How To Be Louise, I was newlywed to Mr. Green, the man I’d met at FOOD. Yes, I’d wanted this husband so I could have children with him but I dared to believe that if I could get my career going before having a baby, there would be enough money for help so that I could ‘have it all’: I could have a child and continue to pursue my dream of making indie films.

One May afternoon, en route to the post office to mail off a film to a film festival, Sara Driver and Jim Jarmusch crossed my path, their rolling luggage behind them. They were headed to JFK to go to Cannes with Down By Law. Not long after, I saw Spike Lee on the nightly news. He was outside the theatre where his first feature She’s Gotta Have It was playing. They were developing international reputations. They were getting paid. I decided that if I was ever going to turn filmmaking into a career and have children, I’d have to figure out how to make a feature.

But I didn’t have any obvious source of funding much less the connections or the chutzpah to pitch: the budget for my feature would have to be on a shoestring. My first two shorts had been inspired by What’s Up Tiger Lily and Rose Hobart: they were made by recutting rejected lab prints in the editing room where I worked. I’d go back to that idea! And I’d shoot some new material with an actor or two and intercut that to make sense of the found footage. All I’d need was a few thousand dollars.

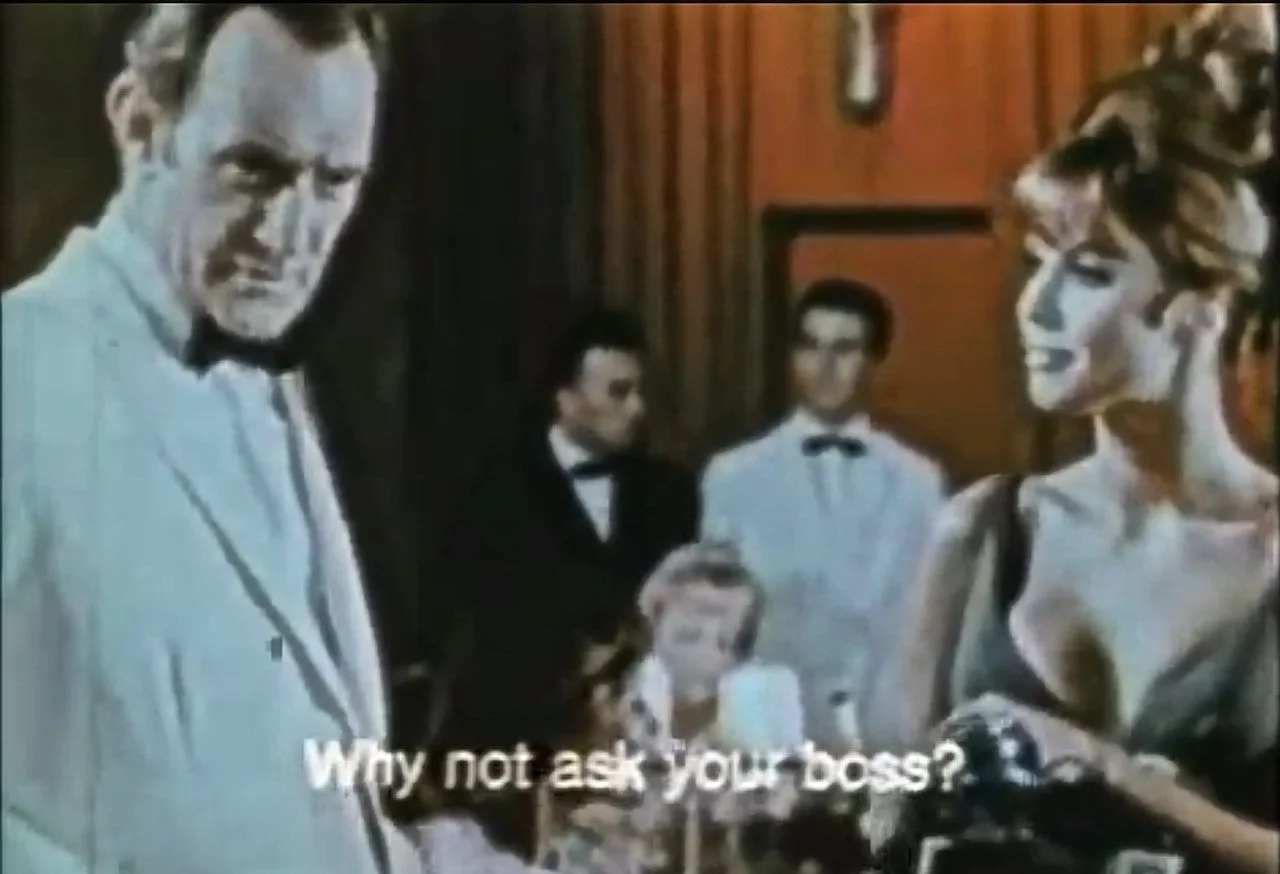

Louise Smells A Rat (1982) was made by duplicating a few shots from The Poppy Is Also a Flower starring Senta Berger and Trevor Howard and intercutting them with newsreel footage and a shot from Phil Silvers' Sergeant Bilko. Original subtitles and music by Johnny Ventura made it into a different story.

There was a particularly discouraging afternoon when I took my place in line among scores of others to present my proposal for a measly $300 grant. I’d brought my own projector, assembled a 16mm sample reel from rejected lab prints and faced what felt like disparaging and hostile questions from this Brooklyn arts organization.

Soon after, reading in bed on a Sunday night, tears started leaking from my eyes. I’m not a person who cries easily, but the steepness of the cliff I was trying to scale and the difficulty of the challenge was suddenly clear. “What is it, Annie?” I answered Mr. Green with sobs and more and louder sobs, eventually losing all control. “What am I supposed to do? Give up this idea of making a feature? Should I try to get a job at an advertising agency and make a lot of money? Or have a bunch of kids? I can’t take it anymore! I’m getting bitter! I’m stuck!” Mr. Green put his arm around me and I cried myself to sleep, confused. I felt broken.

And that night I had a dream that changed my life. I was in a low-ceilinged kitchen right out of the 1950’s. There was a witch in the kitchen, her hair was wild and she was intense, pointing a long skinny arm and finger off into the distance. She was forceful: “Don’t stop now! You’re almost there!”

I woke the next morning with a new confidence. Suddenly I could take the big and little steps to get going. And that message from the witch carried me through the next four years it took to make this film.

As I write this, I’m still scratching my head over the fact that the power came to me after a total breakdown and surrender. It was only after letting go of all my self-discipline, strength, force, will and control that I had the clarity and felt the confidence to do the job. That it was in allowing myself to be overwhelmed by the utterly corny and embarrassing fact of ’feelings’ is a lesson I’m still trying to learn today. (to be continued)

For instant gratification (you’re gonna love it) click the Like button.